Making transition work for workers

To transition jobs, we need to transition lives and communities by reducing dependencies and re-centrering class knowledge.

A few years ago, during the Bolsonaro government in Brazil, I emphasised how critical it was for ecosocialists to support the strikes and struggles by fossil fuel workers, especially at Petrobras. Sometimes, when working towards just transition, people forget that our objective is to phase out fossil fuels, not the working class responsible for expanding access to energy and feeding our industrial supply. As we attempt to move - as fast and justly as possible - to low-carbon economies, we need to learn that if workers in these industries have been so strategic to our societies, they are just as strategic to our plans for changing everything - especially if we really mean everything!

Blaine O'Neill/Flickr, CC BY-NC

Unfortunately, the big transition plans (when they exist at all) by governments looking to go ‘green’ normally bring in workers through bits of social participation, to ensure consultation procedures are upheld, but the job of actually writing transition programmes, debating projects with ministerial employees and setting out concrete guidelines usually falls into the lap of more traditional academics or private consulting firms, informed by a corporate perspective of transition, paid for with public funds or through international cooperation agreements that hand out foreign experts through “technical assistance” initiatives. It is a reality we know all too well when it comes to “development programmes” in the Global South.

This is no accident. It's a system of knowledge that has emerged from the belief that we are backward and underdeveloped, therefore we need expertise from abroad. It's when the fair demand for access to more advanced technologies and knowledges associated with an industry we did not get a chance to develop quite well due to colonisation and dependent capitalism gets mixed with the notion that this is all the wisdom we need to make transition happen. The result is obvious: communities and workers are seen as victims of the transition, who will pay some sort of cost through green sacrifice zones or shifts in employment, so they should be heard regarding these costs and how to offset them, but expertise regarding planning and what kind of transition paradigm we want at all is placed somewhere else, behind closed doors of statistics and models.

This is a problem for democratic deliberation, in terms of the process behind listening, creation and decision-making. It is also a problem for the content of transition - and this is what my post is about today.

I was recently invited to a workshop in Bogotá, put together by the Progressive International and USO (Unión Sindical Obrera) and co-led by the wonderful Lala Penãranda from Trade Unions for Energy Demoocracy (and with whom I collaborated for this piece for the Energy Transitions: Just and Beyond dossier I edited at Alameda). Besides having the opportunity to see friends and comrades and share perspectives of transition with them, something that caught my eye was the focus on USO having a plan for transition that could be presented to the government, to policymakers and to partners. The effort was not to convince the fossil fuel workers represented by USO that transition was necessary and that they should just play along with it - a tiresome script I've seen played in many spaces throughout my 15 years or so of climate engagement and that, I assure you, goes nowhere and could even undo good work. Rather, the objective was to build on USO's conviction that the climate crisis is real, that it is already affecting their jobs and the role of fossil fuels in the Colombian economy, towards creating a plan, a set of guidelines that could be presented to the union workers at large in order to consolidate the position. Later, at the end of the workshop, we met with senator Isabel Cristina Zuleta and she further emphasised the importance of making sure this process led somewhere concrete: for our allies in Congress (anywhere in the world), it is much easier to make the case for transition and to fight denialists if we're the ones promoting the narrative of change, not just accepting it. This also means rejecting the view that these cohorts of workers are victims of the transition, which is something far-right parties have used to gain ground and votes by appealing to old formats of job creation and security. When we support fossil fuel workers in their plan to transition, we help to reposition them as problem-solvers, not obstacles to necessary change.

It is an insight that helps us understand where things went wrong in Global North countries that implemented decarbonisation projects in specific sectors without full worker participation and without a public plan for utilities and the establishment of energy as a right. If workers in the fossil fuel industry worldwide have come to understand transition as a threat to their jobs and livelihoods, this is partly the fault of the same actors pushing for transition in some way or another. This is why it is so key to bring the working class perspective from the beginning, not just at the point where we discuss and adjust impacts. In the Global South, it also offers an opportunity to show how a division between environmentalists on one side and fossil fuel workers on the other is blurry at best. Our workers have been subject to years of poor regulations, unsafe working conditions, risk of accidents, and are all too familiar with the impacts of ecocide when operations are not fully supported by public investment (or are completely privatised). Our workers are quite aware that the communities where they live usually become economically dependent on the big industrial activities in their surrounding. They are part of these communities, so they know of the health impacts on their children and they have come to understand how detrimental it is to perpetuate dependencies on activities that we should phase out in order to mitigate climate change. The issue is: when decarbonisation comes knocking at their door, it usually means economic restructuring, fear of job losses (and weakening of their unions), relocation plans that sound more like forced displacement and a complete uprooting of their lives.

This means that workers in these industries are not, by nature, denialists - even if sometimes they're painted so due to their opposition or resistance to greening in their sectors. These workers, unionised or not, are not part of an isolated category in industry that is alienated from the impacts of climate change and ecological catastrophe. The strange claim by some Global North academics that places the (industrial) working class and the so-called marginalised or frontline communities in completely different categories is just not applicable to the structure of periphery work in the Global South. It reads as a very weird, artificial, differentiation that does not really help with alliances or strategy - for that matter. It divorces production from nature in ways analogous to capitalism, giving the impression that we can reduce the whole of the transition to matters of employment, and hurts our great potential to change everything by engaging with the radical transformation of production throughout the value chain, both nationally and internationally.

I've become kind of allergic to this idea that we need to centre industrial workers instead of marginalised communities in the transition debate if we are to be successful, not just because I've seen the power of resistance and push for alternatives by communities fighting big extractivist projects, but also because I know that, ultimately, there is a lot of confluence in tactics and horizons across the subaltern classes. This debate inspired me to write an academic article a year ago (which you can read for free over here), on the need to build just transition paradigms that work everywhere. The point is to understand that if we reduce transition only to decarbonisation and the carbon metric, and if we treat matters of justice only in terms of guaranteeing that those at risk of losing their jobs will get to keep it somehow in the same industry, now greener, we are forgetting about actually fighting the major contradiction between capital and nature that brought us here in the first place: the metabolic rift.

It is neither acceptable nor really intelligent to treat transition as tiny little pieces of change, in isolated parts of the industry, because nature does not work that way. Our current system of production is based on taking without giving, which creates this ever more irreparable rift in our ecosocial metabolism, leading to bigger crises that capital may try to answer through technology and more inequality in order to prolongue its hegemony, but will ultimately fail into global catastrophe. Since our job on the Left - ecosocialists especially - is to prevent this, we need to do it through holistic and internationalist strategy. And we do it not just because we like the ideal of total emancipation and uniting workers across the globe expressed by Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto back in the 1800s. We need to do it this way, because the majority of the people who will be impacted by transition are precisely the ones with the power to execute it without falling prey to false and partial solutions.

This should inform how we organise our struggles to highlight their convergence, not their differences. When we do this, we're able to explore and create the elements of transition that can bring short-term gains to workers, rather than this promise of a sustainable future paid with present sacrifice. Of course, there are costs to the transition, but if we offset them with an array of benefits, both immediate and in the long run, transition becomes something desirable rather than something to put up with.

We must keep advancing how the perceive and promote a good life, paying attention to the historical warning that, in the Global South, we could never develop like the Global North, which benefitted from unequal ecological and economic exchange, from the value and exploitation of nature and workers right here on the periphery. It also means breaking free from these little boxes of organising, where we say that union workers need to fight for their own membership, Indigenous peoples for their own territory, app drivers against Uber, migrants against unfair governments and border control… When we try to unite them, we usually say they should stand in solidarity with each other, as in caring for the other’s struggle is the right thing to do from a liberation standpoint. But when it comes to transition and repairing the ecosocial metabolism, our lesson is that it is all the same struggle, which makes the job of each level of sector of organising a lot harder. You can't simply claim a working class victory when you push for more jobs for building EVs for the workers in the automobile industry, if it means heavier extractivist pressures on workers mining for strategic minerals and on ecosystems already vulnerable to centuries of pillaging.

When creating unified internationalist strategies, there's no room for othering.

A perspective of transition from the margins calls for the understanding that to transition industries, we also need to transition organisations. This is the best approach to expand strategies beyond specific cohorts, turning solidarity into something organic rather than a burden, in ways to push for alternatives free from green colonialism and other traps that use transition and decarbonisation as tools for maintaining unequal economic and ecological exchange.

It shows us that workers in the fossil fuel industry are strategic not simply because their industry will change radically with transition, but also because they are really well-positioned to reframe how we approach energy sovereignty (in production and consumption), energy as a right (not dictated by the commodity consensus), the relationship between energy and the territory (how we live in it and how we approach the natural goods we extract and transform into resources), and the role of the petrochemical industry in so many other sectors (fertilisers, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, packaging, construction, and so on…). But I really disagree with readings that acknowledge this only to treat unions and workers as inflexible cohorts that are not open to changing their structures, their view of jobs and the impact of their activities, especially by detaching unions from the international network working class organisations. These readings are way too economistic, and often, when based in the Global North, tainted by chauvinistic nationalist views of working class power that will place the needs and desires of workers in the Global North, which are not immune to consumeristic and imperial influences, above those in the Global South.

Rather, my point is that: if workers in fossil fuels influence the production of so many sectors, we're also compelled to explore how current forms of organising sometimes keep workers bound by economistic concerns (something Antonio Gramsci warned us about many decades ago) in ways that are perhaps too rigid. It is why when workers at FUP in Brazil or USO in Colombia talk about the transition of Petrobras and Ecopetrol, respectively, from fossil fuel companies to 100% public energy companies, this is a demand for sovereignty beyond production, but for rearranging everything - including their unions as energy unions, so they can be strengthened by accommodating new types of jobs and new workers that will join along the way. Yes, in transition, certain roles will become obsolete, and we need to be the ones to plan its obsolescence by transitioning jobs and the organisations that support workers’ rights and energy sovereignty in the most just ways.

Since great strategic value brings great responsibility, I was really glad to hear interventions at the workshop by two USO leaders, Moisés Baron and Ariel Diaz, on how the inequalities of development that expose how Global North, imperialist countries, have contributed to most of the climate crisis cannot serve as an excuse to sit back and wait for them to fix everything for everyone. This is something I've been approaching as “ecosystemic responsibility". Whereas the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” is important from the standpoint of setting different emissions targets country-by-country, it cannot be used by Global South countries to overly delay its duty to act.

It really boggles my mind when I see so many respected progressive leaders in the Global South use this differentiation as an excuse to prolongue our dependence on fossil fuels, as if the atmosphere would take into account whether additional greenhouse gases came from the United States or from Argentina when initiating a process of extreme weather events. Not only do droughts and hurricanes fail to choose where they happen based on historical emissions, but one must be really trapped under fossil fuel hegemony to ignore that the more a country delays its mitigation and adaption tasks, the less prepared its economy will be for the impacts of climate change. The way value will be produced in 2050 will be different from a 2025 economy: either because most of the world accelerated its transition and won't need fossil-based goods anymore, or because everyone took so much of their sweet time and the piling up of crises in the polycrisis has generated so much chaos that older industries are vulnerable and cannot keep up.

This is a matter of sovereignty - the ultimate kind! So when organised workers decide they want to be a part of the transition conversation, this is not just about their jobs or adapting their industry to new demands. It is about restructuring so much of society to help us navigate away from the climate crisis and create industries and sectors that are sustainable ecologically and economically. It is about achieving sovereignty beyond the expiry date imposed by climate warming and capitalist crises.

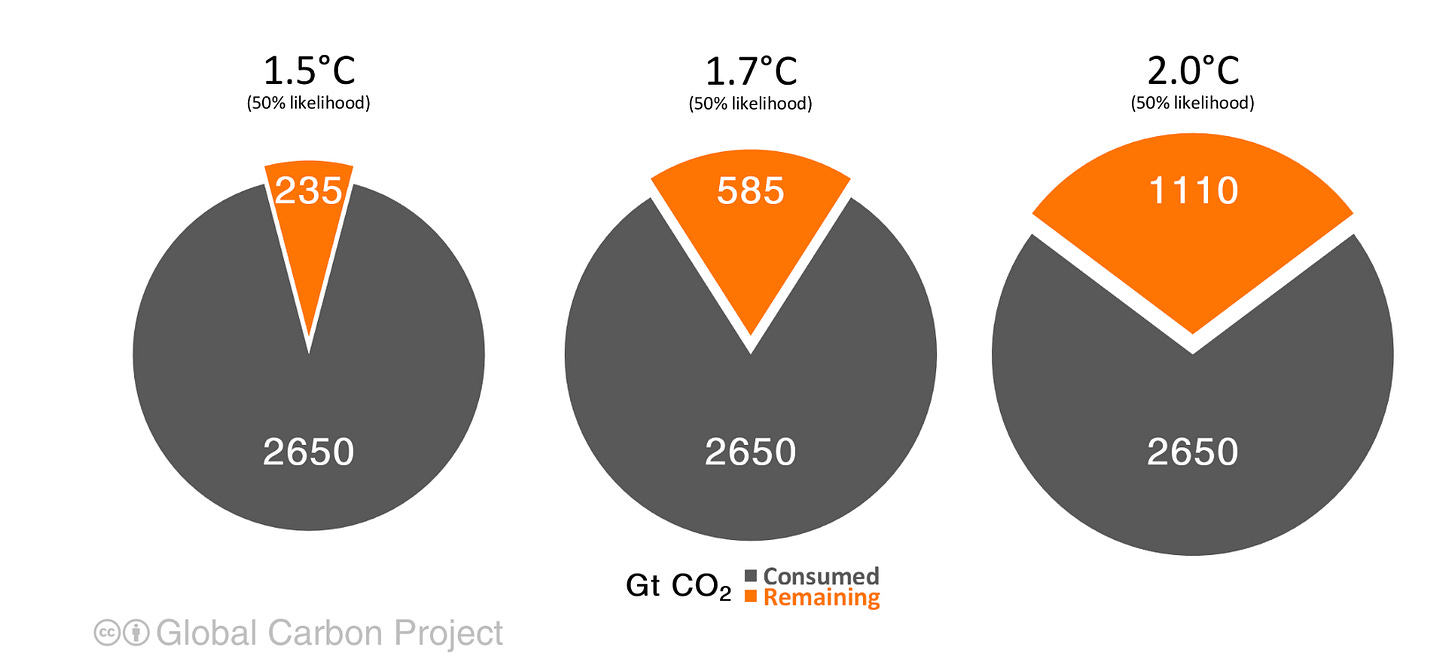

With this in mind, I wanted to support our comrades at USO with tools to articulate the room to grow and to act in Colombia. Transition demands investment and it demands specific types of growth. Because of this, I try to emphasise the role that selective degrowth and divestment can play in our economies, reducing domestic and international dependencies, to ensure that as a global society we finally adhere to the planetary boundaries and limits of what is left in our global emissions budget if we are to be serious at all about the 1.5ºC and 2.0ºC warming values we discuss so much.

The words degrowth and divestment are sometimes scary, but I argue that they are so only if used frivolously outside of a plan. But our point is to have a plan for transition, which must organise the phase-out of certain economic activities in order to make room for others to grow. If we are trying to stay within the orange zone, this is really a job of adjusting - always, internationally. It calls for reducing dependencies at home and abroad and for strong tools for international coordination (something my friend and colleague at TIDE Oxford Amir Lebdioui explored here) that can help us ensure that transition can make sense everywhere. It is also a means for countries in the Global South to really value what we offer to the global economy, by playing to our strengths in terms of primary resources and potential for green industrialisation, as argued by Fadhel Kaboub - who also joined us in Colombia! - through his work on debt and sovereignty.

The reduction of dependencies from the Global South and the Global North can be done through delinking strategies for green industrialisation. This perspective has become quite popular in Latin America, with governments in Brazil, Colombia, Chile and Mexico betting on national development plans that associate transition with industrial development that will help trade balances by reducing the role of primary good exports in their economy and allowing for local production of technology and industrial products. While this is indeed good from the perspective of fighting dependent capitalism and how vulnerable it makes us to global fluctuations and imperialist economic tools, it absolutely has to be paired with a post-extractivist understanding if we are to really prevent further metabolic rifts and, hopefully, start repairing current ones.

One of the major flaws and deficits from current paradigms of sovereignty by leftist organisations and governments in the Global South is the idea that our sovereignty depends on our right to explore our own resources - but not really to protect our ecosystems. It is just not feasible to expect a growing global population to rise collectively to the consumption levels promoted by the imperial mode of living of the North - which authors Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen warn have never even been possible to all residents of the capitalist core. Therefore, delinking and green industrialisation will fail if it simply treats extractivism as a structure of economic dependence on primary goods for exports instead of a system that pillages nature for unconstrained production of things - many of which are unnecessary to a good life, break without repair, and lead to waste at levels never imagined before. This is why I'm partial to sovereignty strategies for delinking coupled with selective degrowth, in the Global South, so we can exercise not only our right to develop the materials we extract, but also to choose how much of it is necessary, for whom, and for what purpose. It is actually how I answered a question at the workshop on the impacts of lithium extraction and growing demand for electrification: I'd much rather see regulation that determines the destiny of our minerals for residences, hospitals and necessary industrial purposes, than to fancy electric individual vehicles that distract us from the expansion of public electric mobility. Real sovereignty, for me, is about full determination and autonomy, which fundamentally requires to set our priorities for transition.

But what about domestic dependencies? Things we need to produce to keep up with our own demands in our countries.

Allow me to offer what I think is a useful example of a major dependency on fossil gas output in Latin America: our usage of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), derived from fossil gas1 processing and crude oil refinery process, as a cooking fuel. One of the reasons many fossil fuel producing countries in the Global South argue that we need to increase fuel production - and that this expansion is not incompatible with transition - is because it is necessary not only for electricity and industrial usage, but also in residences, affecting tens of millions of people at the same time.

In Brazil, in Colombia, and in many other countries, LPG has been the answer to provide people, especially in urban areas, with more convenient and safer cooking. One of the data we had for growing impoverishment and inequality under the Bolsonaro government was in fact that people were going back to using firewood or other unsafe fuel for cooking, unable to purchase “gás de cozinha” under his governments horrible fuel pricing rules that benefited foreign shareholders over Brazilian people. This is why one of our current social welfare programs, strengthened under president Lula, is actually a “vale gás” - a direct voucher program that should help about 17 million families cook in Brazil in 2025 with gas-based stoves by subsidising LPG access. In terms of fossil fuels: this is a domestic dependency.

So, of course, when imaginary threats of shutting down fossil fuel production overnight make their way into common sense, one would say: “So, do you want people to go back to firewood? Do you???”

The answer, of course, is no. Precisely because it is ‘no’, transition implies transforming supply as well as demand. And you know who knows that? Workers in the fossil fuel industry, since they supply LPG at work and use LPG at home. And this is why are comrades at USO highlighted this issue at our activity.

A few years ago, Colombia's UPME advanced plans on phasing-out firewood use (thePlan Nacional de Sustitución de Leña) in Colombian households and there was even a section on moving towards electrical induction cooktops. Of course, as is the case with firewood, you can't just take something away without promoting alternatives: incentives for producing other types of stove and for consumers to purchase/access these other stoves. This is the kind of planning that acknowledges that transition is a process and that it needs to be incentivised. Governments do this all of the time to support industries they want to see grow - sometimes directly subsiding the private sector despite its failures to truly contribute to development. So, why not establish a big national program for clean cooking? This involves various sectors: Research & Development, manufacturing and industrial production of domestic appliances, subsidies and even educational programs. Ecuador, for instance, has been trying something in this direction for a while.

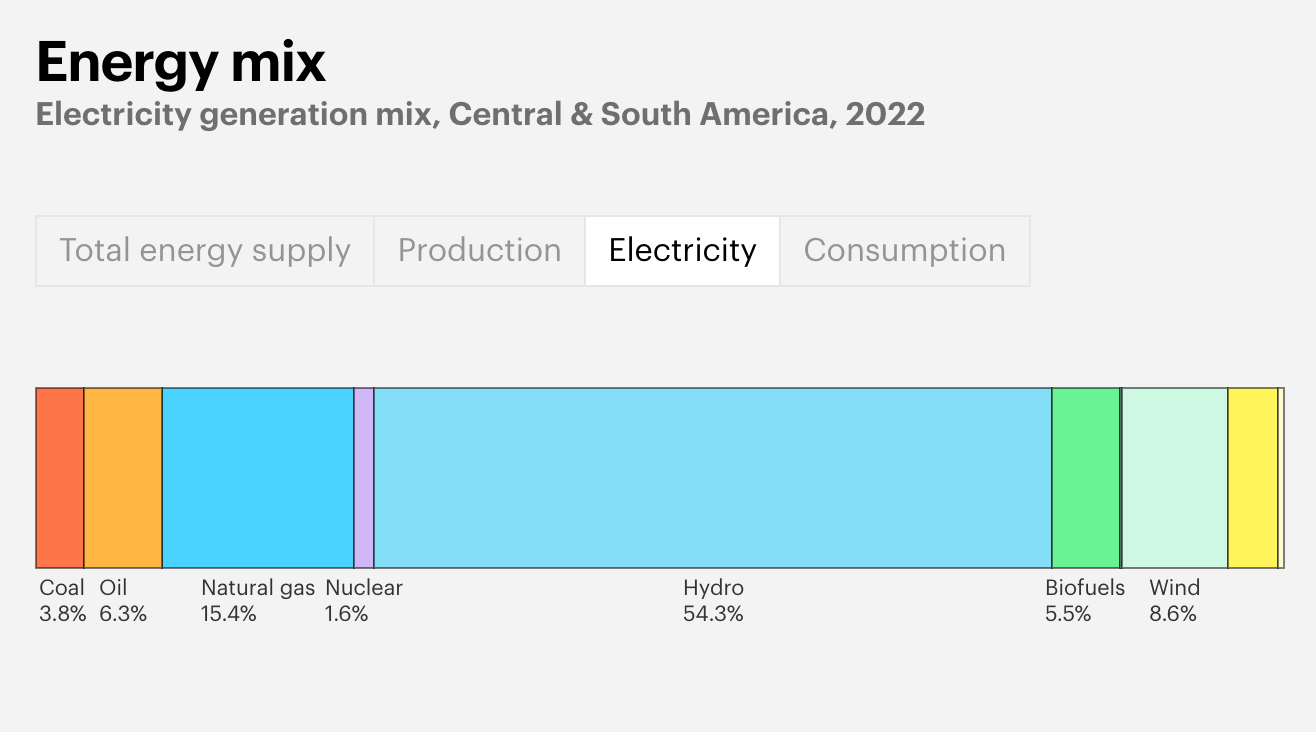

In countries where the electrical matrix is already mostly low-carbon, as is the case of many in Latin America due to a mix of hydroelectric dams, solar and wind, not only are we phasing out the demand for LPG, but we are also ensuring that the alternative is cleaner. Obviously, this only works if governments resist the urge to add more thermoelectric power plants (using fossil gas!) to the matrix in their plans for energy security, which shows us the importance to coordinate transition across sectors.

Is it complicated? Very much so! But the difficulty in this process has long been used to simply accept our current dependencies and normalise an eternal demand for fossil fuels. Well, if green capitalists are daring to invest in knowledge and technologies to reduce their dependencies on plastic, for example, it is just unwise to avoid this route because our governments and societies are used to fossil fuels in our daily operations.

To promote these changes, we need to properly acknowledge that workers are not just pieces of the industries that need to be transformed. They are also the people who will see their whole lives change as a result of the transition. Because of this, it is important to build transition plans through active listening and direct knowledge of the fears, desires, hopes, insecurities and anxieties that have affected workers that are used to hearing about transition as expert-generated plans from above. Hoping to contribute to this methodology that help to understand, from the base upwards, the knowledge gaps in transition, here's a few examples of a couple of areas suggested in my recent exchange with USO, where working class knowledge in the fossil fuel industry should be central to transition planning:

Areas of technical cooperation from workers to governments - planning and implementation

Working and living conditions - Privileged knowledge of reality

Retraining, downsizing (early pensions), and labour gap/demand analysis (curricular planning and transformation/formal training)

This part is perhaps the most important and immediate. Rather than treating these as jobs that will disappear, we need to plan so that workers don't! As the industry transitions, certain roles will be in higher demand, others will become obsolete. It is key to map out where they are and work with these workers on where retraining is desirable, where early pensions would be preferable, and where new skills should be built directly into university and technical curricula.

Job quality and workers' rights: decent work

Gap analysis/worker demands (planning and curriculum transformation/formal training)

Worker support to transition (including education and training debate)

Reduction of working time without prejudice to wages

More unionisation, but also including workers outside the unions (victories in the class struggle)

Cross-cutting policies: workers also live in their communities and territories - they are also affected by dirty or irresponsible industries and will be affected by the economic changes of the energy transition.

Decarbonisation partnerships: national and regional - Changes in the productive matrix of emissions and analysis of opportunities for cooperation and regional coordination

Fighting our historical emissions in agriculture (push for agro-ecological agrarian reform - decreasing dependence on imported or local petrochemical fertilisers, which also generate greenhouse gases in addition to other problems of the monoculture agrarian model).

Cross-cutting policies for rural and urban workers

Broad view of technological challenges - does technological collaboration from the North serve the interests of our peoples or the demands for products from outside?

Analysis of production gaps between groups of workers in the region.

Development of studies and legislative work for a 100% public pathway for energy companies.

Debates for harm reduction programmes. Example: identifyng strategic use of green hydrogen in their operations (not for commodity exports), technological changes for emissions reduction and carbon storage, more productive research to support rejection of extreme energies (i.e.: fracking).

Plan for gradual decommissioning of fossil fuels - Plan the reduction of demand for fossil fuels together with the structural transformation of supply

Recognising current dependencies with the aim of advancing the transition on fair terms in each country.

Decreasing internal consumption dependencies, mainly on extreme energies (‘Demand is not inflexible’ - domestic demand can be encouraged to change)

Redesigning of processes, technologies and logistic chains - looking at damage reduction and the search for alternatives in all economic sectors (beyond energy) that use resources from the petrochemical industry.

What is really truly wonderful is that unions have partnerships and internal capacity to better develop debates in all of these areas. What is really truly unfair is that, sometimes, governments will pay millions of dollars for foreign academics without any ties to movement building, and corporate consulting companies to produce data and recommendations in all of these areas, only to present them to workers at a later stage. It feels backwards, since how can you expect consensus if you only reach those most affected and central to these fields at final stages of consultation, not co-creation?

(and I'm not even mentioning how, sometimes, Global North countries are the ones footing the bill, choosing the experts and directing the results in the name of “cooperation”, but with their own interests at heart.)

Unfortunately, the colonial hierarchy of knowledge and expertise continues to operate in the Global South, even though we have direct expertise of our living realities and beautiful movement debates on the horizons we want to explore to escape the Anthropocene. To fight this, we need to stop positioning ourselves as groups to be consulted after the fact, after the central decisions have been made, and to promote our unions and our movements as the true experts in the just transition.

I hope this reflection contributes to furthering our debates on how to make it happen.

Ps: if you made it to the end of this 4,500 word+ reflection, maybe you'll like this other one on internationalist ecosocialist strategy from a couple of years back. Feedback I've gotten on it has really helped to shape my research and activist agenda on transitions.

Fossil gas is mostly called “natural gas", but I belong to the camp that emphasises that it is of course a fossil fuel. Let's stop naturalising it.

If you're interested in work that bridges the degrowth and delinking debate, here's a few links that help:

- a straightforward reflection by Bill Mitchell on the implications for Global North/Global South strategies https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=61989

- an amazing book chapter by Mariano Féliz engaging with Marxist Dependency Theory critiques, which I use a lot in teaching https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110778359-023/html?lang=en

- great article by Jason Hickel, Morena Lemos and Felix Barbour on the role of unequal exchange of labour in global growth https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-49687-y (in fact, one of my major critiques of the chauvinistic approach to union strategy in the Global North is the refusal to even touch on how this unequal exchange has driven workers apart internationally, promoting division and preventing coordinated action)