Green colonial shades of cooperation

The fine line between international cooperation and colonialism is blurred green

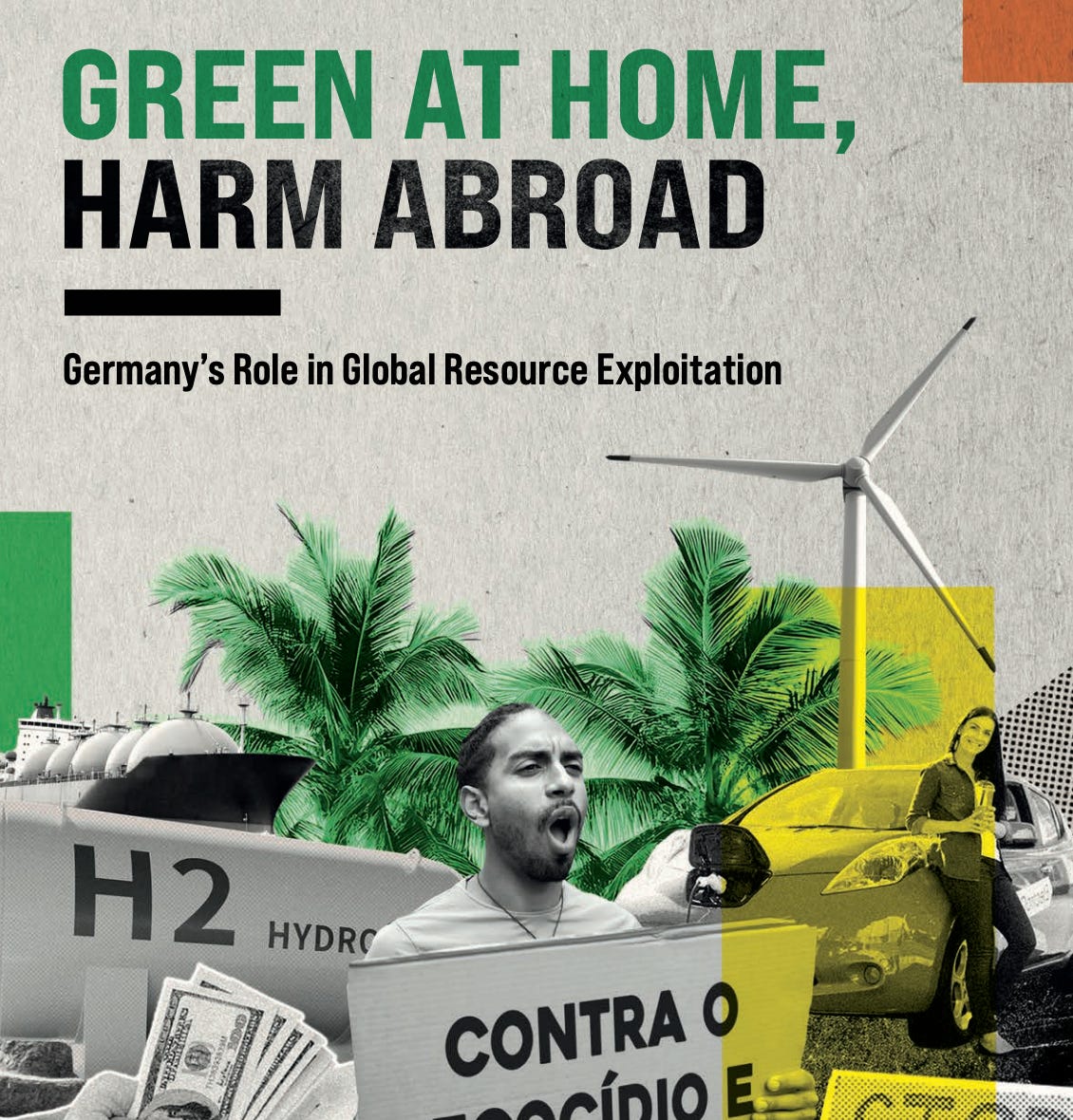

A new study is out, examining the role of Germany in “green” projects in the Global South. The report contains many case studies that examine the new era of bilateral and multilateral cooperation and investments and how it incentivises processes that ensure Global North priorities when it comes to energy and development. It is titled “Green at Home, Harm Abroad” and it is the work of a great team at the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. You can download it in English and for free here (and I hear other translations are in order, including the Portuguese one).

I've been doing work on the dangers of green colonialism for a while, in an attempt to show that previous tendencies by Global South states to try to emulate development patterns from the North (and failing) are now rebooted through a line of green industrial policy, green developmentalism, and commercial dealings that ensure access to our resources by Global North countries, while also limiting our imagination and prospects for alternative development that reconciles the planetary limits with higher quality of life. I was given the opportunity to write the preface for this study, and I was able to elaborate a bit more on it:

“Because these green initiatives operate within the current rules of capitalist accumulation, the global disparities of energy demand and consumption, the impacts of new technologies, the negative effects of supposedly green infrastructure and projects (leading to old and new sacrifice zones), and the economic growth imperative are left out of the conversation. Not only that, but the different meanings of development are taken for granted. Cooperation between states, which sounds benevolent and beneficial in theory, often means providing technical, industrial and technological assistance that contributes to a specific version of development. This technocratic veil provides legitimacy to models that continue to occupy, displace, and negatively impact entire regions in the name of development, but now as green development.” (Fernandes, 2025, p. 6-7)

I really enjoy researching green industrial policy not only because it is necessary, but also because I firmly believe that Global South scholars and activists can create and tell our own path of access to industrial goods without the fancy and false promises made by the North that continue to treat resources as infinite, even when they acknowledge “planetary limits". This happens because the “decarbonisation consensus” (shout out to Breno and Maristella for their great work on this!) will reckon with climate emissions and its thresholds, but chooses to ignore other ecological limits, negative impacts and the abundance of sacrifice zones generated in the name of development.

So in my collaboration with other Global South researchers (and a few excellent Global North allies), I really want to ask the questions: is technological transfer enough to bridge the gap and prevent the Global North from kicking away the ladder, or should we also be claiming for different technologies, with local development, and with different purposes? Do we really want to simply industrialise our strategic minerals ourselves, only to end up making batteries for individual EVs in the Musk-filled supply chain, or should we be planning and defining priorities of usage to ensure that we don't exploit everything and find a balance between ecological needs and other material production needs?

This is also very important for our reflections on jobs in the just transition. I published a long analysis on this already:

But a key matter I could emphasise here is education. One of the things that emerged in the case studies by the RLS publication is how Germany is in cooperations with ministries in the Global South to shape a green curriculum at the universities. While this is absolutely necessary, to ensure that we are already capacitating new workers into a transformed industry, without needing to retrain and move jobs, why is it that we need a foreign country, with its resources, to strike a deal to influence this new curriculum? Don't we have here an issue with methodology, intervention, but also the danger of misguided purpose? So, I added to the preface:

“These practices raise questions about the structure of decision-making in such projects and the level of autonomy local ministries and public servants exercise on projects and objectives set by countries like Germany. Moreover, many of these projects can also involve the private consultancy services of foreign companies, as is the case with a €5.5-million Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) project with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Labour in Brazil on green employment and curriculum (GIZ 2024).” (Fernandes, 2025, p. 8)

The fact is that not everything that is “green” is the kind of green we need when applying principles of just transition and confronting green capitalism. In a few months, I'll be able to share with you the excellent articles written by our collaborators on the Nacla issue on “Green capitalism in the Americas” I am co-editing. It will help to expose the traps behind false solutions and financial mechanisms, hopefully making the case that we need to go green, yes, but we need to paint it ourselves and in a truly sustainable way.

Sexta-feira me deparei com esta matéria aqui:

https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2025/07/30/indigenas-ocupam-fazenda-contra-avanco-da-exploracao-do-litio-no-vale-do-jequitinhonha/

Aí fui pesquisar sobre as empresas e me deparei com isso aqui:

https://agenciadenoticias.bndes.gov.br/industria/BNDES-aprova-R$-4867-milhoes-para-Sigma-Lithium-beneficiar-litio-de-forma-sustentavel/

Seu texto cai como uma luva: que economia verde é essa? Que projeto econômico e de sustentabilidade queremos? No fundo é tudo capitalismo...

Em tempo, quem tiver estômago:

https://www.brasilmineral.com.br/maiores/sigmalithium