Ecological sovereignty: from mutual annihilation to true planetary longevity?

When fossil fuel expansion is justified in the name of national sovereignty, you know states have lost touch with the climate reality.

A couple of years ago, I published a short piece named “Sovereignty and the polycrisis” to reflect on how limited this framework has been in contexts of global disaster: wars, pandemics, climate change. The Westphalian state sovereignty system still dominates understandings of resource use and extraction, territorial control, borders, economic growth and even cooperation.

Part of my concern to address this comes from the fact that, since science is not neutral, the climate and social science I practice is deeply influenced by what's going in the Global South, particularly my home country, Brazil.

Many eyes are on Brazil right now, given that it is hosting COP30 in the Amazonian city of Belém. Symbolically, it is a win. Brazil had been expected to host a COP before, but this effort was crushed by the denialism and pariah behaviour of the far-right Jair Bolsonaro government (2019-2022). Moreover, after a few years of COPs in countries denying freedom and space to grassroots and democratic voices for climate justice, Brazil's young democracy could offer more opportunities for popular dissent. This is specially sought after by Indigenous peoples, whose territories continue to be violated by agribusiness, mining, oil companies (both state and private), and whose claims of sovereignty are downplayed even by governments friendly to environmental issues and native populations. After all, the real sovereign can only be the state.

This is evident in the current battle between Indigenous voices and Lula's government in Brazil. Opposition to drilling for oil in the Equatorial Margin, a delicate marine ecosystem close to the Amazon Forest, is big. Indigenous leaders have voiced their opposition, including Cacique Raoni, who accompanied Lula up the presidential ramp during inauguration in 2023. Environmental groups and NGOs have showed how much a disaster this could be, both to the local ecosystem (which is, of course, connected to nearby ecosystems) and climate change in general.

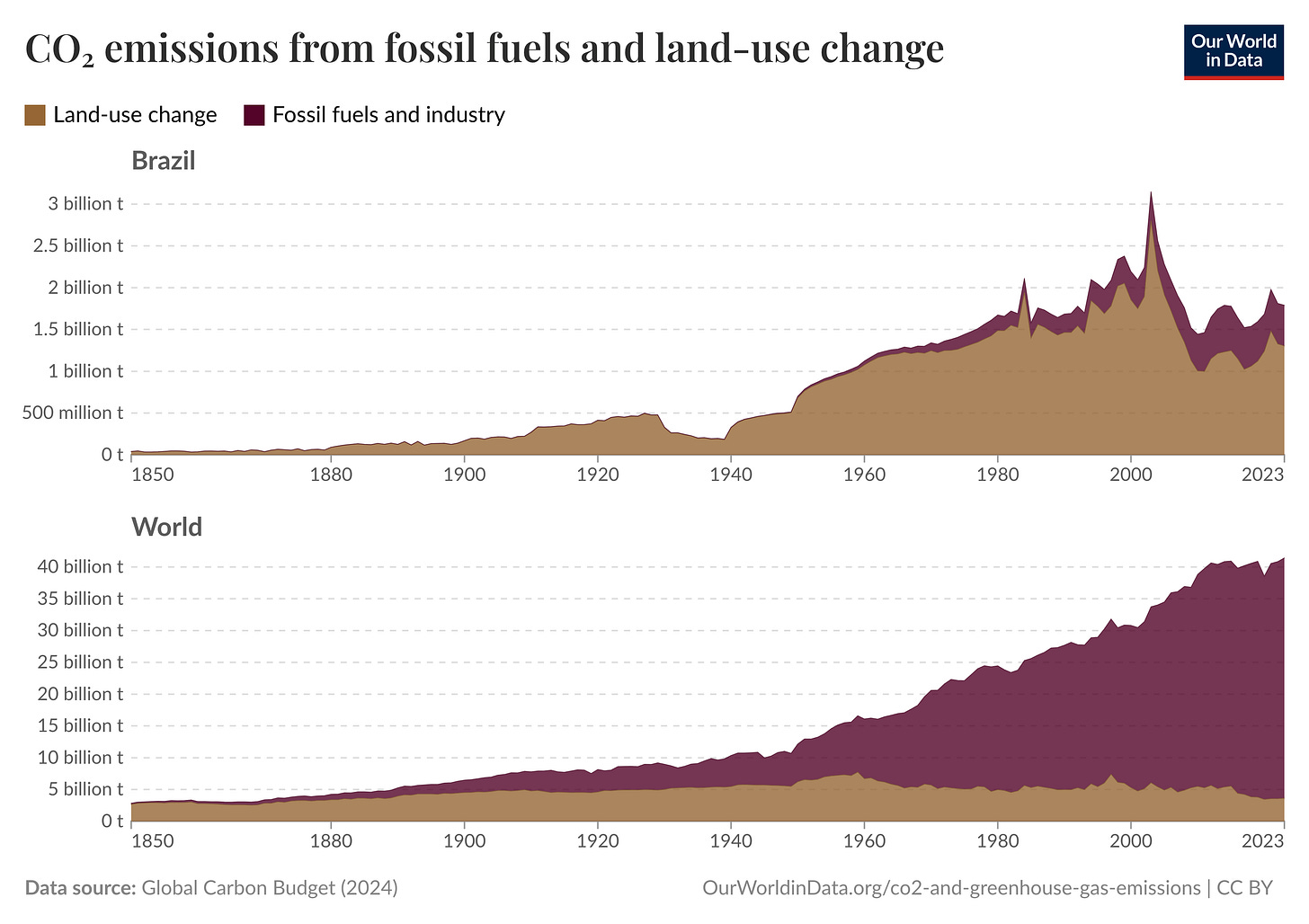

Brazil is a bit of a shadow climate villain: its colonial period left a legacy of extreme land inequality and an economy based on the production of primary goods. It means that since 1822, when Brazil obtained independence from Portugal, the country failed to shift directions over use of land and to fight deforestation, with a strong period of land-use related emissions that began in the last century and continues until today:

When I point this out, I usually hear (from other Brazilians and from Global South colleagues) that Brazil cannot be held responsible for this, since it's colonialism's fault. Yet, emissions are clearly tracked to Brazil's Republic and the modern ideal that occupied both right and left-wing leadership over how to use the land, how to extract natural goods as resources, and the growing dependence on commodity exports for capital income.

This is to say: we did not create our dependent capitalism, but we sure perfected it - at the expense of Indigenous and quilombola communities, rural workers and peasants, and of course, our forests and global climate. Brazil may be a post-colonial state, in historical terms, but it never really decolonised. Our Indigenous peoples and descendants of formerly enslaved peoples are still waiting on proper reparations and for their perspectives to count beyond symbolic acts of representation. In fact, if their voices began to be treated as fully legitimate by the state, and not only when demands coincide with state development priorities, this would already be of big help.

However, the truth is that our territorial-based peoples are still treated as enemies of “development” when they voice their concerns about fossil fuels, mining, mega infrastructure projects and agribusiness expansion.

Political cognitive dissonance over climate and development

We keep hearing from Brazilian leftists that fossil fuels are one thing, deforestation is something else completely. The failure to address climate change as a global catastrophe promoted by greenhouse gas emissions from multiple sources and to acknowledge, as many scientific institutions have begged us to, that our carbon budget is shrinking and emissions cuts should be radical and everywhere is a convenient failure. It lets us play nice, promoting policies that fight deforestation and gives us legitimacy for financial funds that further commodify forests while leaving only a small percentage of the dollars raised for the communities that actually care for them (yes, I'm talking about TFFF and how, unfortunately people read “forever forests” and immediately think it's a good thing rather than another market mechanism).

And when we play nice, we get to conceal all the other problems in how we approach climate: we say that we didn't emit as much from fossil fuels, so we get a “quota” to keep doing it; we say that it's okay that we keep drilling, since we'll export most of it and the emissions won't be ours, so our NDCs will be fine; we say that we need to drill for more oil, because this is how we'll finance our energy transition, but our budget shows that this isn't true; we say that we get to expand fossil fuels, because our electricity matrix is already so decarbonised due to hydropower, as if fossil fuels were a problem only for electricity production; and we say that we need to keep drilling for all the oil we can find, because: (1) others are doing it; (2) if we don't, then the imperialists will come and will use our resources.

I went over some of these arguments in my recent essay for The BREAK-DOWN and, later, during my talk for their podcast with Adrienne Buller. But let me stress the last point, since it connects for these last three years of work I've been doing on the concept of sovereignty and the need to re-work it completely if we are to survive the odds of global climate catastrophe.

The way Global South countries, especially under progressive governments, have weaponised the anti-imperialist struggle to justify fossil fuel expansion is not only problematic of an argument, it is also suicidal.

For some reason, everybody loves science when it is about pointing out the denialism behind Trump or Bolsonaro. But state developmentalists on the left don't like to acknowledge their own tendencies towards denialisms. Climate change is a global problem created through inequality and felt through inequality. This statement should be the main motivator for radical ecological transition based on strong reparations and compensation mechanisms. Acknowledging climate science should lead to a strong push for global fossil fuel phase-out, where the only debate would be over how to make it just and gradual to avoid collapse and more pain for developing countries.

But fossil fuel phase-out is not really on their negotiation table. Oil-dependent emergent economies are right to demand that the rich countries carry most of the burden, but if we are to wait for the people who broke the planet to be the ones with the strongest initiative to save us all, then we are fooling ourselves. In addition, it is highly problematic to address the need to make the transition just and equitable as just a matter of who does it first. To quote myself in the introduction to our “Energy Transitions: Just and Beyond” dossier:

“To believe that a fast Global North transition allows the Global South more time to do so in the future, after having its own turn with conventional fossil-fuel pathways of development, is to promote development and sovereignty with an expiry date. By then, the climate will have worsened for all, but the conditions for mitigation and adaptation in the Global South will be even more adverse, with the Global North having benefited from cheap extraction and technology without any reduction in its energy footprint or adjustment for energy sufficiency.”

Right now, the Global South is divided into at least two groups: the ones demanding full transition and capacity (including reparations) to do their own; and the ones demanding transition in principle, but hoping others do it first to buy time to squeeze every last drop of oil of each available field.

Unfortunately, whereas countries like Tuvalu and Colombia seem to be leaning towards the first group, Brazil has joined OPEC+ and pushed hard for a license to drill in the Equatorial Margin despite major outcry. In typical “tunnel vision” - especially connected to the Amazon forest - Lula went as far as to say that drilling in the area was not a problem, because it wasn't that close to the forest anyway. It's almost as if Brazil's climate duty was to the Amazon and nothing else.

If only that were true, it would mean that we'd be actually confronting the power of agribusiness that has devastated Brazil's Cerrado, is expanding its business to the Amazon at alarming rates, while greenwashing itself through flimsy claims of “regenerative livestock farming” and bogus carbon credits. But the opposite is true: we are funding agribusiness more than ever and Lula even met with Trump to defend the interests of Brazil's largest meat corporation, JBS.

But don't you worry! This is all very very very anti-imperialist!

At least this is what many leftist leaders, economists and pundits tell us. Their reasoning for anti-imperialism is based on a very narrow and chauvinistic view of sovereignty not only incompatible with the ecological challenged posed today, but also deeply colonial in relation to other sovereign claims to territory and ecosystems.

It is based on the idea that if resources are available, they ought to be used by the state for the good of all. The principle is not a bad one and I fully support it, for example, when it comes to public sanitation, public electricity, public transportation. In fact, I support it because I would like this to mean not just state-control, but full decommodification of goods and services that improve workers’ lives and empower peoples and communities who actually take care of our planet and indirectly make our lives possible and healthier.

But when it comes to fossil fuels, there is a big difference between asserting state control over resources against imperialist threats and equating control with extraction and full use.

For starters, it is not the fact that a country is drilling and promoting its own national-state operations that will protect them from the United States big global oil-grab. Venezuela is proof of this. What ensures that oil-rich countries such as Saudi Arabia hold their ground is a combination of state and capital capacities, including regional alliances and common investment deals, that makes them less of an easy target.

In the Brazilian case, it is not like Trump could just arrive here anytime, say that since we are not drilling within our oil-rich margins, so he will! I'm sure this kind of stuff crosses the mind of someone like Trump anytime, but oil-grabs come in many forms, including when Brazil's National Petroleum Agency is the one auctioning oil field for foreign corporations to exploit in alliance with Petrobras. Foreign powers have learned that they can access our oil, our minerals, our water, our soil and - they hope - our renewables through cooperation, deals and joint ventures. So, in such cases, when we do the drilling, when we open new extraction frontiers, we are actually opening doors for foreign use of our resource. The difference is that we keep telling ourselves that we are doing it in our own terms, not under the boots of imperial domination. But this is another lie that we tell ourselves to pretend our big national investments aren't following cues from international market pressures that might let us into the big leagues, but only as long as we play nice.

We should aim for “ecological sovereignty” instead

Our issue is that even though the anti-imperialist struggle is real and should be at the centre of how we evaluate state action in the polycrisis, this anti-imperialist struggle needs to be ecological too. The idea that the only way we can assert our sovereignty is by depleting resources to ensure capital income at the expense of global climate - with horrible consequences even for ourselves - is actually not very different from how the imperialists define their own sovereignty claims.

Earlier in the year, I wrote a chapter about this for a book that will come out next year (edited by Dena Freeman at Shanghai University) on precisely this topic. I go over the failures of framing sovereignty through a capital-nation-state Borromean ring (drawing on the brilliant work of Kojin Karatani) and then proceed to make my case for ecologising sovereignty. Of course, I can't go over elements of it here, but since I've been dropping “ecological sovereignty” or “popular ecological sovereignty” as my choice of conceptual framework in many other articles and pieces recently, I wanted to bring in two short paragraphs from my chapter, which also inform another paper I'm working on right now (hint: so if you have feedback on this, let me know now - it's how we advance work collectively):

“When sovereignty is framed through capitalist interests, the incentive for international solidarity is weakened and cooperation ends up limited to short-run economic and security goals. Thus, an eco-territorial internationalism, which includes states but is not restricted by statism, has to look for sovereign interests of many peoples at once, requiring an alternative frame and conceptual basis for sovereignty. “Ecological sovereignty” contributes to this alternative by focusing on interdependence with the rest of the planet in relation to the ecological and material conditions we share at various scales.

Ecological sovereignty is an encompassing frame that learns from building and interweaving different kinds of sovereignties globally - food sovereignty, energy sovereignty, territorial sovereignty – to inform another kind of economic thinking, less aimed at comparative advantage and more focused on global immunity to catastrophe. As a concept of sovereignty fit for building alternatives, based on “permanence, the capacity to stay and thrive”, ecological sovereignty helps to ensure mutual survival, while setting the tenets of a more “solidaristic mode of living””

I want to emphasise ecological sovereignty because I fear efforts for internationalist just transitions will fail if those promoting alternatives (progressive, leftist, socialist ones) keep insisting that we can do this by playing the game the way imperialists do. As of now, whereas Indigenous peoples demand sovereignty over their territories, states and NGOs are more likely to offer them participation in carbon markets than to fight the classes that continue to invade even legally recognised Indigenous land. Nowadays, when we say we want to protect an ecosystem, we find a way to attach a number to it, put it under the trust of some fund, and even use it to leverage our debts (as was the case of loss of sovereignty in Galapagos in a debt-for-nature swap that, in the end, has nothing to do with debt justice).

A framework of sovereignty that is based on ecological understandings is capable of overcoming tunnel visions that have favoured false market solutions to climate change and treating nature as divisible pieces that can be commodified at will. Ecological sovereignty looks not only at climate change, but at all planetary boundaries. It confronts the imperative of capitalist growth and identifies where we can reduce waste and damaging economic activities to make room for good and desirable growth, the kind of expansion that helps to restore Earth's metabolism while improving lives for a majority. Ecological sovereignty connects to other important debates on sovereignty as a way to guide their goals through staying under planetary limits: on food sovereignty, it means agroecology, restoring dignity to rural life, agrarian reform where needed, less meat production and more diverse foods on our plates; on digital sovereignty, it means addressing the excessive energy demand by Big Tech billionaires and their data centers so that peoples and states have control of their own data to limit how much is produced and how we use energy, land and water to upkeep it.

Protesters clash with COP30 security

Unfortunately, this is not the view of sovereignty at the core of COP30 today. Yes, there is more diverse representation. Yes, there is even more room for climate scientists to warn us all of the dangers of delayed action. But the parties in this Conference of the Parties still view sovereignty as a zero-sum game. This is understandable, as we are driven to self-protection and should not lower our guard when the far-right is taking over some many states all over the world. But this also means it is a good opportunity to reframe our demands away from market-solutions, kick the polluters out of the conferences, and learn from Indigenous dissent that shows us that the territory is not about a piece of property, but about the creation of life.

This is the basis for overcoming the contradictions of our anti-imperialist approach, where we challenge our opponents, but not the rules of their game. Ecological sovereignty will require that we impose some big “No's” on what can be exploited, by whom, for what purpose, for how long and these questions matter a lot, since they can qualify what we can do with climate financing to actually make climate action more equitable. It is about laying foundations for true longevity, something that should be at the core of how we interpret the word “sovereignty".

Right now, all states want their sovereignty and no one wants to be big losers in the polycrisis. But as long as we keep framing the hard tasks of transition through exploitation rather than custodianship, any sovereignty attained will always be sovereignty with an expiry date. Of course, it may expire for some faster than others, but our fight shouldn't be to be the last survivors in this mutual annihilation system, but the ones to break the system and lead us all into a common and good life.

Ótimo! Muitas passagens para destacar. Mas essa aqui conecta com algo que venho falando e escrevendo: "Ecological sovereignty will require that we impose some big “No's” on what can be exploited"

O pragmatismo tomou conta do "fazer política". Tudo é calculo - político, de lucro/prejuízo. Ninguém mais é capaz de falar "não". Não existem mais limites. O pragmatismo virou a carta coringa, o super trunfo.

Como bem colocado no texto, é a lógica do discurso: "se não explorarmos o petróleo alguém o fará".

É pragmatismo com derrotismo.

Por fim, fico tentando imaginar o sentimento dos povos da Amazônia: no dia da posse, subindo a rampa. No dia seguinte, descendo a ladeira junto com as brocas à procura de petróleo. E depois se perguntam sobre a razão dos sentimentos de ressentimento e ódio que dominam nossas sociedades

Sabrina, que excelente saber que está trabalhando no conceito de soberania ecológica! Como alguém da área do Direito Internacional, eu sempre me incomodo demais com os significados clássicos de soberania e vivo tentando incoporar outras perspectivas (popular, alimentar etc.) no conceito. Ansiosa para poder incluir a soberania ecológica daqui pra frente. Obrigada pelas suas sempre inspiradoras contribuições para o modo de pensar soluções pra esse mundo complicado em que vivemos <3